The Labour party, if elected, has committed to setting up GB Energy, a new state-owned investment in the energy system. As a UK taxpayer and as a clean energy obsessive, I want to ensure that my money, if being invested, is being employed as well as it can be for maximum social, environmental and economic impact.

In this piece I consider what we know about GB energy, I outline the risks of simply setting up an investment vehicle without consideration of how it fits in with the UK energy governance landscape and I make proposals for what it could probably do best. I argue that it would be best placed to focus on system coordination, local energy investment and the tricky issue of heat decarbonisation and gas network decline. I think it should basically do four things:

- Act as a home for the NESO which should itself have an explicit role as an energy agency, removing this ownership and potential conflict from the DESNZ Secretary of State.

- Act as an investor in high risk and uncertain industries to drive innovation and bring in private money. These investments should be subject to thorough needs analysis.

- Become the owner of the UK gas distribution networks, reclaiming their value while planning their wind down.

- Work with local authorities to develop local heat networks and support local investments in renewables – all in coordination with the gas network wind down.

What do we know about GB Energy?

Not much is known about it, other than it will have £8.3 billion of funding in the next parliament, with a chunk of that for community energy. Apparently it will have three initial priorities (these are directly lifted from the webpage):

‘Co-investing in new technologies: Great British Energy will help speed up and scale the deployment of new technologies, with public investment helping to crowd in investment in areas like floating offshore wind, tidal power and hydrogen as they develop into mature technologies.

Scale and accelerate mature technologies: Great British Energy will also help scale and accelerate the roll-out of mature technologies, like wind, solar and nuclear. It will partner with existing private sector firms to speed up deployment of mature renewable technologies to meet our ambitious clean power timelines. It will also build organisational capability and expertise to deliver energy megaprojects like nuclear power stations, reducing project and construction risk.

Scale up municipal and community energy: GB Energy will partner with energy companies, local authorities and cooperatives to develop 8GWs small-scale and medium-scale community energy projects. Profits will flow directly back into local communities to cut bills, not to the shareholders of foreign companies. This will help to create a more decentralised energy system, with more local generation and ownership, and will help to create a more resilient energy system.’

James and Josh at Flint Global have helpfully put together how it may operate in this detailed piece, suggesting it could do three things:

- Act as a state energy investment vehicle.

- Be a publicly owned energy investor.

- Act as a net zero delivery agency.

I generally agree with their assessment, but I, as a UK taxpayer, and potential GB Energy shareholder, have some thoughts about specifically what it should and shouldn’t do. And I actually think it could be a great vehicle to drive down emissions from buildings and to act as a coordinator of the transition.

Back to basics

Renationalising energy is popular amongst the general public. ‘66% of the public want to see energy in public ownership, including 62% of Conservative voters.’

There’s potential for a big shift here, and that makes the risks particularly high.

A new government may go a lot further than they are currently suggesting. The previous Labour leadership wanted to nationalize huge chunks of the system.

There are three main reasons government’s may want parts of the energy system to be nationally owned.

- Because the investment is too high risk or too long term therefore putting off investors or demanding very high costs of capital. Ports for offshore wind is a good example of long term; if the government pulls the plug on offshore wind, then you’re stuck with a useless and very costly port. Floating offshore wind is a good example of high risk – it’s new technology not proven at scale.

- Because it’s not appropriate for private capital to be used. Parts of nuclear decommissioning/waste management is a good example, when for example the only goal is safety, at (almost) any cost and profit focused motives may not be appropriate.

- Because of ideological reasons. The UK tends to have greater levels of private involvement in the energy system than many of our European neighbours. Privatisation was done because it was thought to be a good thing and the government wanted some cash but actually comparative analysis of whether this has been a good thing is not really available and there is often disagreement. I can certainly point to examples of state or municipal ownership that are better than private e.g. Dutch energy networks.

If you put public money into areas that are low risk and where it is appropriate for private capital to be used, you risk crowding out private investment in the areas where it makes most sense (and where money is cheapest, giving the cheapest outcome for consumers).

Under James and Josh’s first option, the government could just buy shares in energy companies. This would be fine and could give a chunk of profits to GB taxpayers, but why not just pay down government debt? There’s about £2.7 trillion of it, which comes with a major finance cost. Paying the interest on our debt cost £8.6 billion in April. Would investments in energy make us more than paying off debt? This seems like a bit of a non-starter, especially when private capital seems keen (subject to policy certainty). As is also pointed out, we already have the UK Infrastructure Bank.

Option two sees the government becoming a publicly owned energy investor. Floating offshore wind has been mentioned here and I’m told by wind people, this would make some sense to really get the ball rolling on this rapidly innovating sector. But this is a big and risky new thing for the government to do. Partnerships and expertise would be needed and we’re starting from a low baseline.

The third option sees GB energy as a net zero delivery agency a sort of convenor and planner – it’s difficult to see how this makes us money!? But we also already have the new National Energy System Operator (NESO) which is expected to do some of this work.

Take stock before you start spending

Before investing a pound of my own money, I’d want to assess the lay of the land and firstly I’d take a look at what we are already doing with government capital investments/ownership in energy.

- The UK Infrastructure Bank, with £22 billion of capitalization and fully owned by the Treasury, already exists to crowd in private investment across energy, transport, digital, water and waste and has a focus on regional or local growth. This seems to already do part of the energy investment vehicle bit – it could just be expanded.

- UK Government Investments (the ultimate shareholder of the UK Infrastructure Bank) has a number of other ownerships, though these are mostly associated with nuclear decommissioning, liabilities and fuel enrichment. Paying for the running of these nuclear services makes up a huge share of the DESNZ budget already – about £6 billion a year. The liability here is about £124 billion.

- The big change which is due imminently is that the National Energy System Operator (NESO), a new body which combines the Electricity System Operator and the Gas System Operator, is to be state owned with the DESNZ Secretary of State as the sole shareholder. As well as gas and power system balancing and managing the connections queue, the NESO body will develop a national spatial energy plan, develop a new Regional Energy System Planner (RESP) function and will also offer energy advice on planning and investment to both government and Ofgem. This body will be paid for via bills and regulated by Ofgem, much in the same way that the ESO is currently.

Won’t somebody please think about the governance!?

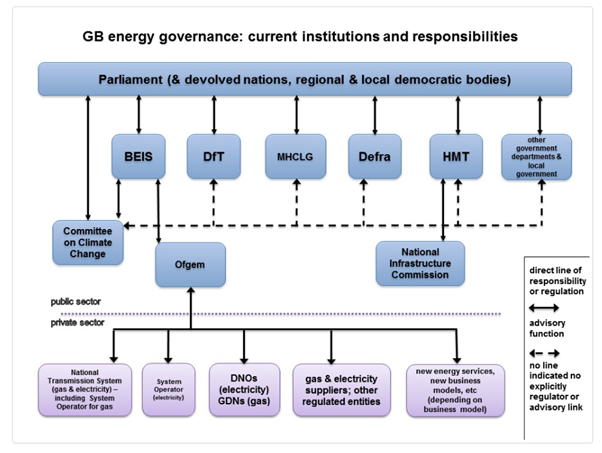

The current shape of the UK’s energy system is extremely complicated. Too complicated. Few understand it fully (I’m sure I don’t). The University of Exeter IGov project led by Professor Catherine Mitchell forensically analysed UK energy governance, over 7 years from 2012 to 2019. The model below from 2019 shows what the governance structure looked like then.

Not much has changed since then, apart from DESNZ was split out from BEIS and ESO is becoming the NESO and being nationalized. But the structure is still difficult, multiple departments are needed to resolve certain issues and there’s no real link to local authorities. This is a major energy policy problem which a new body would just make worse.

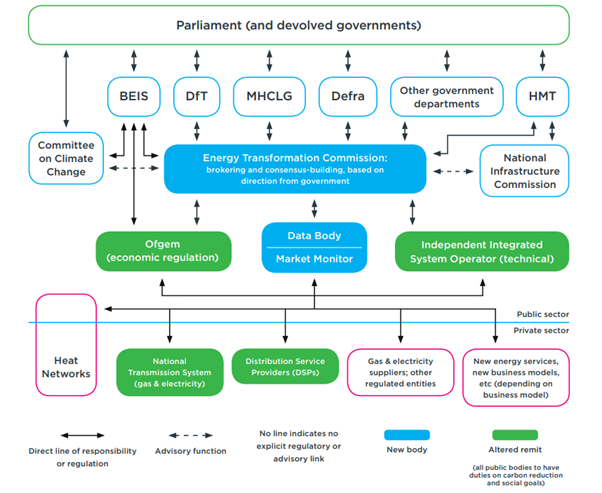

IGov proposed a new model, shown below. Note, this isn’t all the detail. But what the model proposed was much greater consensus building from a new ‘energy transformation comission’, much stronger links to local authorities and an independed system operator among other things. (I’m not doing the project justice with such a brief description, government staff should review this work again).

What we now have, is parts of the model proposed by IGov, but not all of it, and parts not necessarily in the right place. It is surely a little bit odd that the new NESO is owned by the Secretary of State but is regulated by Ofgem on its operations and income with Ofgem effectively reporting to the Secretary of State. This is made more complex by the fact that it has an advisory role – back to Government!

As well as this being really complicated, I’m sure there are going to be issues with conflicts of interest and political interference – it’s just too messy. The UK needs an advisory energy agency of some sort and this function has just been plonked into the NESO albeit with no official name. Genuinely, no-one seems to have oversight of this governance – probably because it’s just too complex.

As a potential shareholder in GB Energy, I’m now worried about all this complexity – who is really in charge? And I’m also worried that my GB Energy shares will make it worse. Where does it fit in? How is it governed?

So what would I do with GB Energy’s money?

Well let’s ignore the actual £8.6 billion number for now, it pales into insignificance compared to some of the numbers I’ve mentioned already and in any case it’s just shifting money from private to public hands. In 2008 government bailed out the banks for £137 billion and provided a trillion of financial guarantees and our energy system is pretty profitable. If we’re going to nationalise bits, let’s think about where it most makes sense and then consider capital after -we’re not going shopping but we’re thinking about maximum value.

So how could GB energy sort out the complex governance and find a place where government money can be most appropriately invested?

- Firstly, GB Energy should take on the ownership of NESO. This is basically a shift from ownership by DESNZ to slightly more arms-length from central government but it feels more appropriate than the NESO being owned by DESNZ and regulated by Ofgem while acting as an energy agency.

- GB Energy should incorporate the new ‘GB Energy Agency’ (my name). We can’t fudge this any longer and for neatness we just need to put planning and expertise in one place. Much of what is needed is already going to be in the NESO and this feels like a good fit. This will do some of the work of the Energy Transformation Commission proposed by IGov.

- Secondly, GB energy should invest where the market won’t. Floating offshore wind is one example where the market needs a kick start but there will be other examples. We absolutely should not make any kneejerk decisions on this – objectivity is needed on what areas specifically need government capital support.

- Third, GB energy should take over the ownership of the gas distribution networks. It’s just not appropriate for foreign money (it’s all foreign owned) to be looking to maximise profits from a sector which needs to rapidly decline and which continues to lobby for false solutions like hydrogen. This operation could ensure all potential asset stranding costs are paid back equitably. To be clear, this would still be regulated by Ofgem and would be a for profit business while investments were recouped. This could help manage some of the current concerns around executive pay and asset stripping.

- Four, GB energy should lend to or invest with local authorities to develop their own wind projects and heat networks.

- Wind investments are vital and are much more likely to be supported by locals if they have a share in them.

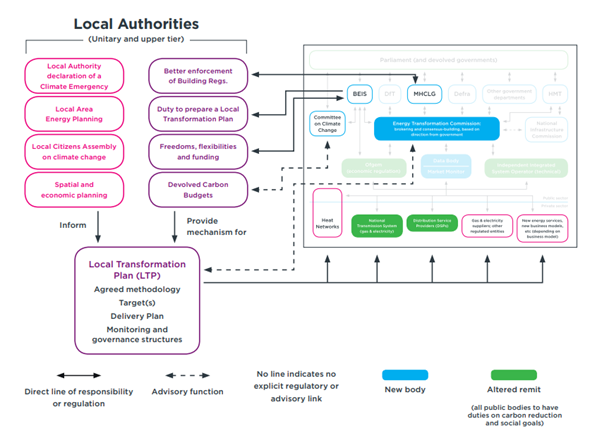

- Local authorities generally need help on energy matters and may struggle to get finance. It makes perfect sense for the development of heat networks (natural monopolies) to be led by local authorities and be owned by these authorities or by government. With GB Energy also owning the gas networks, the phase out of the gas grids could be neatly coordinated with the development of heat networks in urban areas. This would provide a strong new institutional relationship between central and local governments on energy.

What would I not do with GB Energy’s money?

Just putting UK taxpayer money into already profitable projects as an investor does not seem to make sense to me. As I said already, we have a huge debt pile which we are servicing and it’s not clear why government money would be better place buying shares than paying that off. The argument seems to be that GB energy could be the next EDF or Vattenfall but I struggle to see exactly what the benefit is. If we are worried about foreign owned companies making too much profit from UK investments, surely the solution would be to regulate them better.

I’d also keep nuclear well away from GB Energy. The decommissioning costs will need to be paid for years and represent a net cost to the economy. There’s no evidence that new nuclear will be cheap or easy and it’s unlikely to be a major growth sector. The legacy is poor and the scale of this challenge risks derailing GB energy which could be a truly green function. Nuclear could be dead-weight for GB Energy, just as it is for DESNZ.

So what’s my advice to GB Energy?

Back to the published priorities: Priority one makes sense: use government capital to its maximum advantage, to de-risk and crowd in private capital, but the UK infrastructure bank is already doing some of this.

I’m not sure about priority two, unless it’s clear that this will not crowd out or upset private capital, steer well clear. Why take the risk with upsetting something like offshore wind which is growing well but has more practical constraints that money can’t help. Give it certainty and support but not cash – as you would a teenager.

Priority three does makes sense but GB energy needs to ensure it specifically helps with heat networks as these are core to the needed local authority energy investments.

So there are my reformed priorities for GB Energy:

- ‘Co-investing in new technologies: Great British Energy will help speed up and scale the deployment of new technologies, with public investment helping to crowd in investment in areas like floating offshore wind, tidal power and hydrogen as they develop into mature technologies.

- Become the home of the National Energy System Operator and a new GB Energy Agency, pulling together existing and proposed NESO functions into an independent centre of energy expertise.

- Become the owner of UK gas distribution networks to put them on a socially and politically sustainable footing as we transition to cleaner heat over the coming decades and to look after the people who work for them and support them in the transition.

- Scale up municipal and community energy: GB Energy will partner with energy companies, local authorities and cooperatives to develop small-scale and medium-scale community energy projects and to grow local heating solutions in particular heat network. Profits will flow directly back into local communities to cut bills, not to the shareholders of foreign companies. This will help to create a more decentralised energy system, with more local generation and ownership, and will help to create a more resilient energy system.’

Overall, with successful and efficient delivery of parts (but certainly not all) of the UK energy system by the private sector and the UK government already heavily indebted, we need to consider carefully where taxpayer investments are best made. There is undoubtedly a need for greater government intervention in the energy system, but putting money in the wrong places could put up costs for consumers. GB Energy is well placed to drive innovation in cutting edge technologies, to encourage system coordination and expertise via the NESO and to support local authorities develop local energy and clean heating systems while managing the decline of gas infrastructure.

Addendum on the wealth fund: With no details of what the proposed national wealth fund will do, beyond this facebook video of Rachel Reeves I’d just add that this obviously needs to be considered alongside GB energy. There still seems to be some confusion over what a wealth fund is. In my limited experience of sovereign wealth funds, these tend to just be massive government savings accounts. Norway has over a trillion in its fund which it has made mostly from oil and gas. If the Labour proposal is to have a similar fund then I don’t understand why we wouldn’t pay down national debt first. I’ve also confusingly seen suggestions that the wealth fund would be an investment vehicle. Of course, any money put into a wealth fund which comes from energy consumer’s bills means higher bills.

Leave a comment